The Non-fiction Feature

Also in this Monthly Bulletin:

The Fiction Spot: The Plague by Albert Camus

The Product Spot: Jack Black lotion

The Pithy Take & Who Benefits

Steven Johnson, an author of multiple science books, pulls us into 1850s London, where filth is everywhere, bacteria is unknown, and people living on Broad Street are dying of cholera at an alarming rate. He takes us through the steps of Dr. John Snow and clergyman Henry Whitehead as they follow cholera and death, desperately trying to find the cause of the outbreak. Johnson provides not only a heartbreaking mystery (through hair-raising descriptions of London’s rankness) but he also sketches a wider image of how cities came to be.

I think this book is for people who seek to understand: (1) how the unorthodox Snow and Whitehead, through reason and persistence, discovered the source of London’s deadliest cholera outbreak; (2) what happens when sanitation systems fail or don’t exist; and (3) how to take hope, even during the bleakest of times, in how Snow and Whitehead battled the intractable curse of cholera amidst powerful medical superstitions.

The Outline

London – 1854

- 2.5 million people lived within London’s 30-mile circumference.

- This population density was unprecedented at the time, and the techniques for managing it didn’t exist yet: recycling centers, public health departments, and safe sewage removal.

- Efficient waste recycling is crucial for dense concentrations of life to survive.

- The financial cost of waste removal was high; thus, many let excrement accumulate, and there were heaps of feces the size of large houses all throughout London.

- Londoners felt that things could not continue at this pace for long—the metropolitan city, as a concept, was untested and unproven.

The Basics of Cholera

- Cholera is a species of bacterium (Vibrio cholerae).

- Cholera’s first significant effect is serious dehydration and reduced blood circulation.

- Eventually, the heart can’t maintain adequate blood pressure.

- The bowels evacuate vast amounts of water that contain tiny, white particles (and massive quantities of V. cholerae). Vital organs shut down, and within hours the victim is dead.

- Physical contact can’t get a person sick.

- Cholera must be ingested and find its way into the small intestine. Then, another person ingests the bacteria, usually by drinking contaminated water.

- For thousands of years, cholera was kept in check because humans are generally disinclined to consume excrement, and when they did, it was unlikely to happen again.

- But, the contamination of drinking water in urban settlements increased the amount of V. cholerae, which increased the bacteria’s lethality.

- Cholera victims who drink large quantities of water usually survive. But, during this age, there was no consensus on cholera remedies.

Monday, August 28

- The Lewis family lived at 40 Broad Street and had two children. Infant Lewis contracted cholera in late August 1854.

- She began vomiting and emitting watery, green stools. The parents soaked her diapers in water and tossed the water in a cesspool at the front of the house.

John Snow and Henry Whitehead

- John Snow was a famous anesthesiologist (he looked after Queen Victoria).

- He first saw the ravages of cholera in a mine, observed the dreadful sanitary conditions, and noted that the miners defecated where they ate.

- He constantly thought about the possibility that cholera outbreaks were rooted in impoverished social conditions.

- Henry Whitehead was an affable Anglican clergyman and was well acquainted with many residents on Broad Street.

Saturday, September 2

- The Broad Street water pump, located next to 40 Broad Street, consistently attracted a steady stream of visitors.

- Within a few hours, cholera struck hundreds of residents—entire families suffered together in dark, suffocating rooms.

- Cholera could kill by the thousands but it usually took months to unfold.

- Whitehead visited multiple homes and realized that contrary to conventional thought, sanitary conditions weren’t relevant when it came to who became sick with cholera (e.g., some in filthy homes were healthy, some in wealthier, cleaner homes were sick).

- By the end of the day, dozens in the neighborhood were dead.

The state of medicine in 1850s London

- During this time, the medical community was split between the contagionists and the miasmists. Either cholera passed from person to person (as the contagionists believed), like the flu, or it lingered in the “miasma” of unclean spaces.

- London’s official sanitation commissioner, Edwin Chadwick, and the city’s main demographer, William Farr, along with many doctors, were miasmists.

- Snow didn’t believe the miasma theory. In one outbreak, the same doctor attended two cholera patients and he didn’t get sick, so clearly it wasn’t communicated by proximity.

- Snow believed that an unidentified agent caused cholera via ingestion.

- He realized that in past outbreaks, cholera seemed to lurk near water supplies. If miasmists were right, why would cholera devastate one building but leave the one next door unscathed?

Sunday, September 3

- Snow suspected that the high number of casualties, in such a short period of time, meant that there was a central contaminated water source.

- Snow drew samples from pumps in the area, expecting the contaminated water to be cloudy. (Broad Street pump water was clear.)

- Whitehead took some Broad Street pump water, mixed it with brandy, and drank.

- In one day, 70 people in the neighborhood died of cholera.

- Miles away from Broad Street, Susannah Eley and her niece died after drinking Broad Street water, which her children (who lived near the pump) shipped to her.

- There was no other case of cholera in her neighborhood.

Edwin Chadwick

- As sanitation commissioner, Chadwick helped solidify, if not outright invent, the basic structure of modern government: the state should directly protect its citizens’ health and well-being; a centralized group of experts can solve problems that free markets either exacerbate or ignore; public-health issues often require enormous state investment.

- His career is the point of origin for the concept of “big government.”

- Some of the most significant programs he championed had catastrophic effects; thousands of cholera deaths in the 1850s can be directly attributed to his decisions.

- Chadwick pushed for legislation to remove all the filth from houses in a reliable fashion. As such, much street refuse was sent to the Thames, the river where people got their water, and cholera returned with a vengeance.

Monday, September 4

- Snow drew more samples from the Broad Street pump. This time, he saw small white particles in the water.

- In his lab, he found a high presence of chlorides, and he thought they were remnants of decomposed organic matter.

- He also read William Farr’s Weekly Returns of Birth and Deaths (a publication about local demographics). Farr thought Snow’s theory was worth investigating, and he started tracking where people got their water.

Tuesday, September 5

- For every new death, Whitehead heard of a recovery. People attributed their recoveries to consuming large quantities of Broad Street pump water.

- More than 500 residents in the neighborhood died in 5 days.

Wednesday, September 6

- Per Farr’s publication, Snow found out that there were a handful of isolated cases. This was what Snow desperately sought: aberrations.

- Snow’s survey of the neighborhood revealed ten deaths outside the neighborhood.

- Lion Brewery had 70 workers but not a single death–the brewery had a private pipeline and a well.

- The Eley Brothers factory reported that dozens of employees were ill. The Eley brothers’ mother and their cousin had recently died of cholera, but both of them lived far from the area.

- Snow asked if Susannah Eley consumed some of the water, and the brothers stated that they regularly delivered pump water to her.

- Snow concluded that cholera attacked the gut. Thus, cholera was ingested, not inhaled.

- When Whitehead later retraced the week’s events, he found that almost all the survivors who had consumed large quantities of Broad Street water did their drinking after Saturday.

- It was harder to find anyone who drank the pump water earlier in the week because most of them were dead.

- It’s possible that V. cholerae had largely died in the pump by the weekend.

Friday, September 8

- The Board of Governors of St. James Parish held an emergency meeting about the pump. Snow explained the poor survival among people living near the pump, and the unusual survival of those who hadn’t had the water.

- Ultimately, the Board removed the pump handle.

- This was a historical turning point, not just because it ended London’s most explosive cholera outbreak, but also because, for the first time, a public institution made a scientifically-reasoned intervention into a cholera outbreak.

- Removing the pump struck Whitehead as foolish, and he was determined to disprove the theory.

- Ultimately, the Board removed the pump handle.

- In the end, nearly 700 people living within 250 yards of the Broad Street pump died in less than two weeks.

John Snow and Henry Whitehead Join Forces

- The vestry of St. James (parishioners from the local church) formed a committee to investigate the outbreak, which Snow and Whitehead joined.

- Whitehead examined a crucial absence in Snow’s survey: the residents who drank the water but survived.

- As he interviewed more people, his resistance to Snow’s theory faded. People consistently remembered a connection to the Broad Street pump.

- Whitehead was surprised that Snow blamed the outbreak on “special contamination…from the evacuations of cholera patients” that had leaked into the well from a sewer or cesspool.

- If Snow’s theory was correct, Whitehead said, the outbreak should have been a gradual upward slope, rather than a sudden spike followed by a decline. Who had done the contaminating?

- Whitehead was already familiar with baby Lewis’s passing. In Farr’s demographics publication, it said that the baby had diarrhea four days before passing.

- If baby Lewis had been sick for four days, that meant her illness would have predated the outbreak by at least a day, and they lived right next to the pump.

- Whitehead found out that the parents dumped the baby’s soiled diapers into a cesspool in the basement at the front of the house.

- Investigators surveyed the well again. Between the cesspool and the well, they found swampy soil saturated with human filth.

- Whitehead also realized that the other cholera victims didn’t empty their buckets into the Broad Street well; only the Lewis family had that access.

- The connection between the bacteria and well was cut off after baby Lewis died.

- The vestry committee issued a report that vindicated Snow’s original hypothesis.

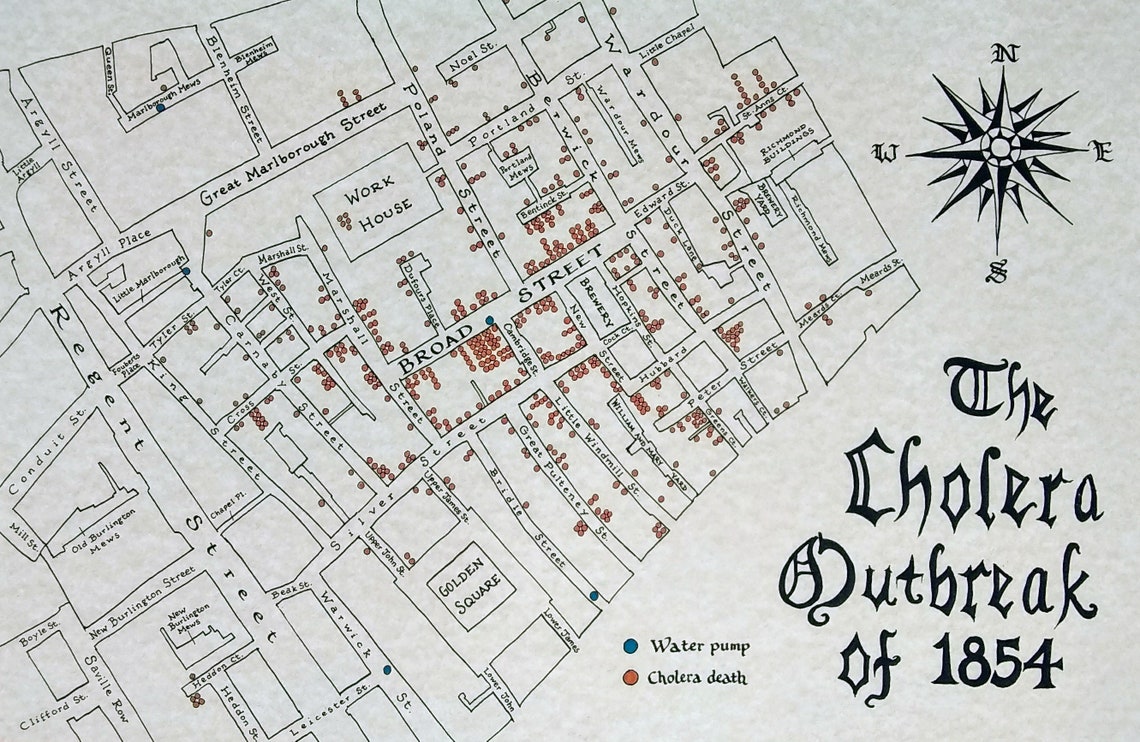

The Ghost Map

- John Snow began working on his first map of the Broad Street outbreak in early fall of 1854, and it became the defining symbol of the entire tragedy.

- The real innovation lay in the data that generated the map, and in the investigation that compiled the data.

- The waterborne theory of cholera became increasingly accepted and the map grew in stature and popularity.

- Snow and Whitehead solved a local mystery that led, ultimately, to a series of global solutions that transformed metropolitan living into a sustainable practice as opposed to a death sentence.

- By 1865, civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette and his team created the most advanced and elaborate sewage system in the world. They constructed 82 miles of sewers, and it remains the backbone of London’s sewer system.

- This is the world that Snow and Whitehead helped make possible: a planet of cities.

- And yet, there is still great concern about viruses and bacteria. Some experts think pandemics are a near inevitability.

- This is why a continued commitment to public health institutions remains one of the most vital roles of states and international bodies.

And More, Including:

- Background about the battle between contagionists and miasmists, and how it led to devastating public health decisions

- Significant details about Snow and Whitehead’s separate but equally determined forays into the houses of cholera victims

- The enormous significance of waste management systems, not only the sophisticated structures used today, but also the “night soil men” and those who made a living out of recycling waste using basic means, and the great value they brought to their cities

- Explanations of how bacteria and viruses are able to mutate so quickly and lethally

- A substantial epilogue about the connectedness of our lives and why public health institutions are ever more paramount

The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic – and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World

Author: Steven Johnson

Publisher: Riverhead Books

Pages: 299 | 2007

Purchase

[If you purchase anything from Bookshop via this link, I get a small percentage at no cost to you.]